Oops! Black Basta ransomware flubs encryption

Researchers at SRLabs have made a decryption tool available for Black Basta ransomware, allowing some victims of the group to decrypt files without paying a ransom. The decryptor works for victims whose files were encrypted between November 2022 and December 2023.

The decryptor, called Black Basta Buster, exploits a flaw in the encryption algorithm used in older versions of the Black Basta group’s ransomware. The bug was fixed by the group in mid-December, probably as a result of the discovery, so it won’t work on the most recent attacks.

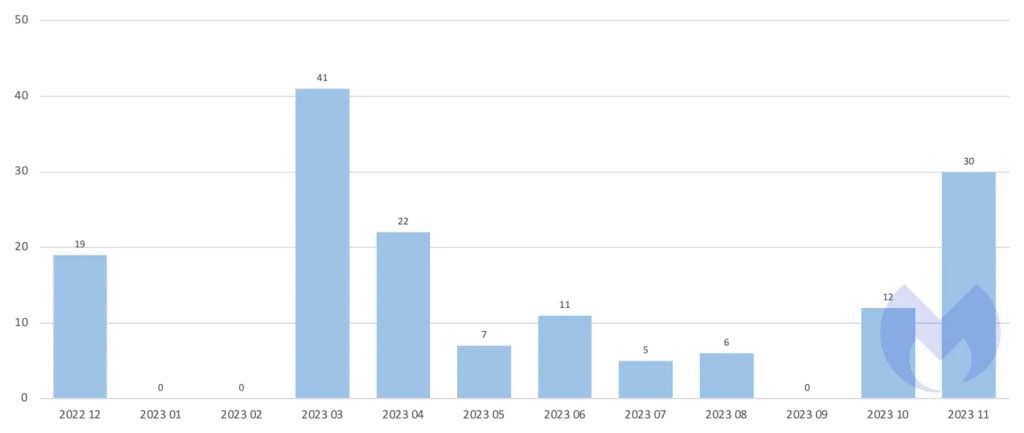

During the period the decryptor works for, the gang was responsible for 153 known attacks (attacks where the victim did not pay a ransom and appeared on Black Basta’s dark web data leak site).

BlackBasta first appeared in April 2022 and is a regular entry in the top 5 most active ransomware groups in our monthly ransomware reviews. Among others, the ransomware has been used to attack organizations like Canada’s Yellow Pages and German arms producer Rheinmetall.

The decryptor comes with a few restrictions due to the nature of the flaw it exploits.

On its Github page for Black Basta Buster, SRLabs explains:

“Files below the size of 5000 bytes cannot be recovered. For files between 5000 bytes and 1GB in size, full recovery is possible. For files larger than 1GB, the first 5000 bytes will be lost but the remainder can be recovered.”

So, how do you recover your files?

The decryptor only works on one file at a time and your best chances are on virtual machine disks. According to SRLabs, virtualised disk images “have a high chance of being recovered, because the actual partitions and their filesystems tend to start later. So the ransomware destroyed the MBR or GPT partition table, but tools such as “testdisk” can often recover or re-generate those.”

Files can be recovered if the plaintext of 64 encrypted bytes is known. The easiest way to establish this is to find a sequence of zeroes in the file. It may be possible to decrypt large files that don’t contain large enough chunks of zero-bytes, but you will need an unencrypted version of the target file. In many cases this will defeat the purpose of decryption, but there may be are edge cases where you have a previous version of the target file that meets the requirements, but does not hold the information you want to decrypt.

On the Github pages you will find several python scripts to help you with the recovery of the encrypted files. Interested parties can find instructions on how to use them in the readme file. This is not an easy process and certainly not something we would recommend using for every encrypted file. Each victim will need to weigh up how useful it is to them.

BleepingComputer reports that some digital forensics companies may have been aware of the flaw and have been assisting clients for months in recovering important files, similar to the way the FBI offered decryption keys to Hive victims after penetrating its computer networks. They may have done the same for ALPHV victims, but this is unconfirmed.

Obviously, it’s better to avoid malicious encryption if you can, so here are some pointers.