Ransomware in the UK, April 2022–March 2023

Threat Intelligence Team

Threat Intelligence Team

This article is based on research by Marcelo Rivero, Malwarebytes’ ransomware specialist, who monitors information published by ransomware gangs on their dark web sites. In this report, “known attacks” are attacks where the victim opted not to pay a ransom. This provides the best overall picture of ransomware activity, but the true number of attacks is far higher.

Between April 2022 and March 2023, the UK was a prime target for ransomware gangs. During that period:

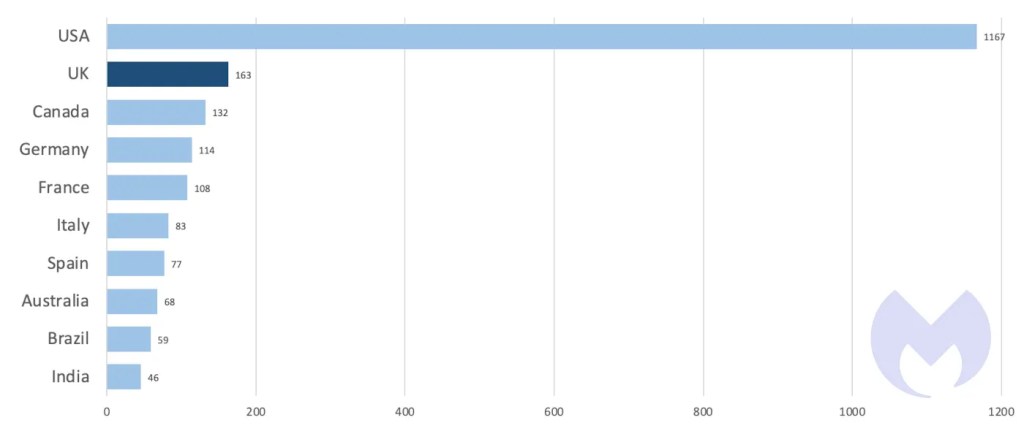

- The UK was the second most attacked country in the world.

- Royal Mail was hit with the largest known ransom demand ever: $80 million.

- The education sector was hit far harder than in other countries.

- The UK was a prime target for Vice Society, which targets education.

In August 2022, a ransomware attack on IT supplier Advanced caused widespread outages across the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), the biggest employer in Europe and the seventh largest in the world. The attack affected services including patient referrals, ambulance dispatch, out-of-hours appointment bookings, mental health services and emergency prescriptions.

Later that year, British newspaper The Guardian experienced a major ransomware attack that shut down part of its IT infrastructure. The Guardian, which operates one of the most visited websites in the world, described the incident as a “highly sophisticated cyberattack involving unauthorised third-party access to parts of our network”, most likely triggered by a successful phishing attempt.

In January 2023, Britain’s multinational postal service, Royal Mail, was attacked by LockBit, arguably the world’s most dangerous ransomware, which demanded the biggest ransom we have ever seen anywhere, in any country: $80 million. Royal Mail rejected the demand, calling it ‘absurd’, and LockBit consequently published the files stolen from the company alongside an illuminating transcript of the negotiation between the two parties.

The UK: Just like the USA

In the 12 months from April 2022 to March 2023, the UK suffered more known ransomware attacks than any country other than the USA. However, the sheer number of ransomware attacks in the USA dwarfs all other countries. Given the disparity between the USA and the UK it would be easy to conclude that ransomware is, first-and-foremost, a USA problem.

It is not.

The USA suffered a little over seven times more attacks in the last twelve months than the UK and it is perhaps not a coincidence that the USA’s economic output, measured by gross domestic product (GDP), was also about seven times larger than the UK.

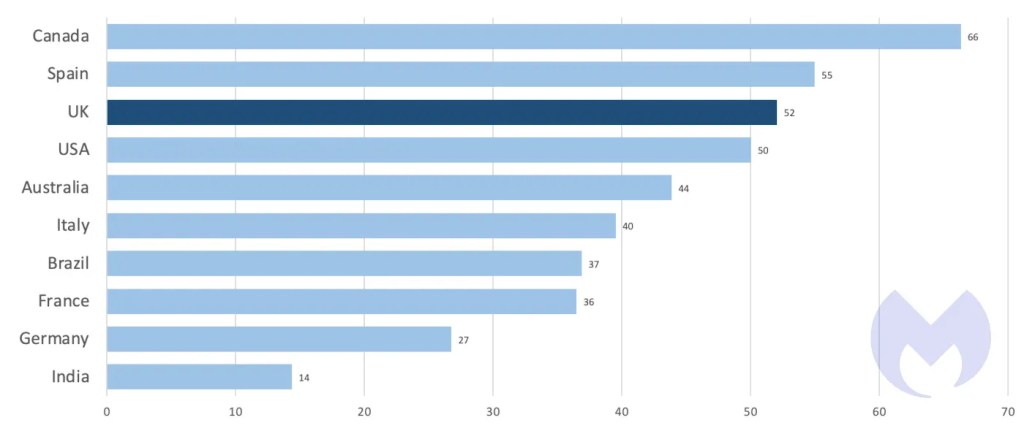

We can account for the difference in the size of countries’ economies by dividing the number of known ransomware attacks by a country’s nominal GDP, which gives us an approximate rate of attacks per $1T of economic output. On that basis, the USA and the UK suffered nearly identical rates of attack, at around 50 known attacks per $1T.

Measured this way, the UK is third, almost a mirror of its Atlantic cousin and quite different from its geographic and economic near neighbours, France and Germany. In other words, on this measure, ransomware gangs appear to make no distinction between the UK and the USA.

Another way to account for the vast difference in size in countries in the top ten is to divide known attacks by each country’s population. On that measure, the UK ranks fourth, and again suffers a far higher rate of attacks than either France or Germany.

The most likely explanation for the difference between the UK, France and Germany is language. To make serious money, ransomware gangs have to be able to attack businesses in the USA. They have to be able to operate inside company networks where things are written in English, understand the value of the English-language data they’ve stolen, and negotiate in English.

However you rank the top ten, English-speaking countries occupy at least three of the top five positions. In the per-capita list they occupy four. It seems that when it comes to ransomware, speaking English may be a serious drawback, which helps ensure the UK is a prime target.

Education, education, education

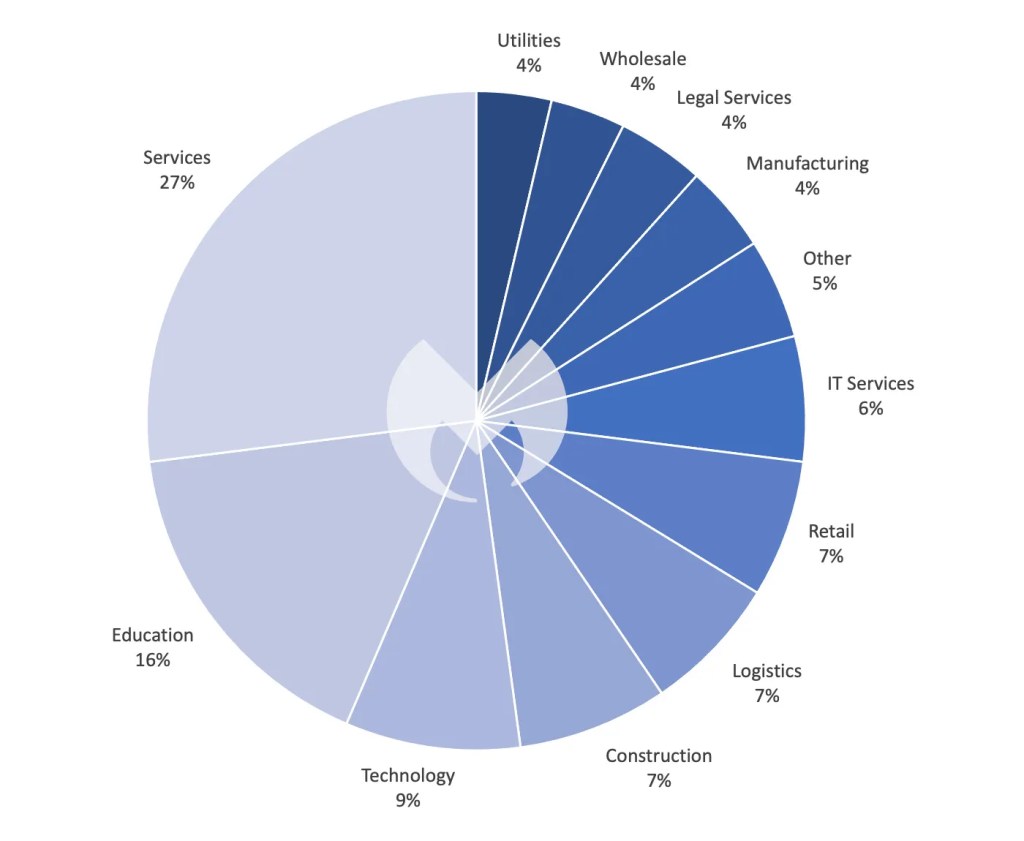

Over the last 12 months, the education sector in the UK suffered far more than in other countries. Education was the target in 16% of known attacks in the UK, but only 4% in France and Germany, and 7% in the USA.

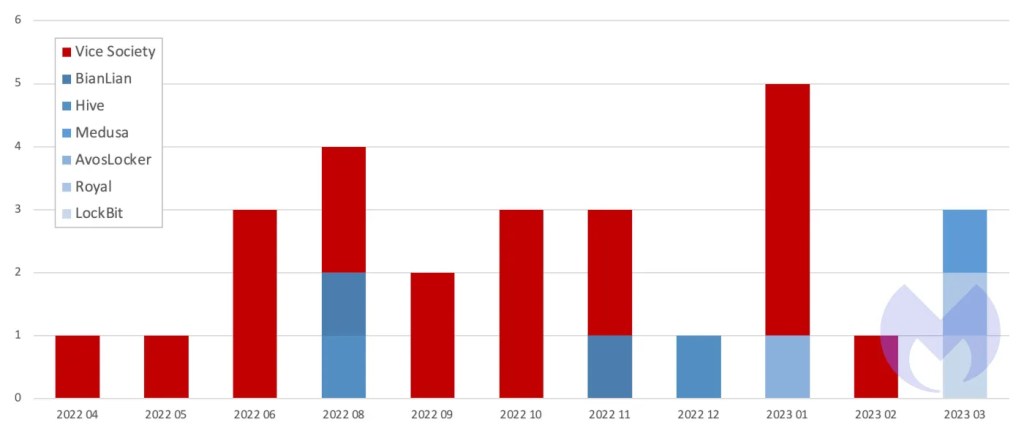

Our data shows that one of the main reasons for this is Vice Society, an extremely dangerous ransomware group with an appetite for the education sector.

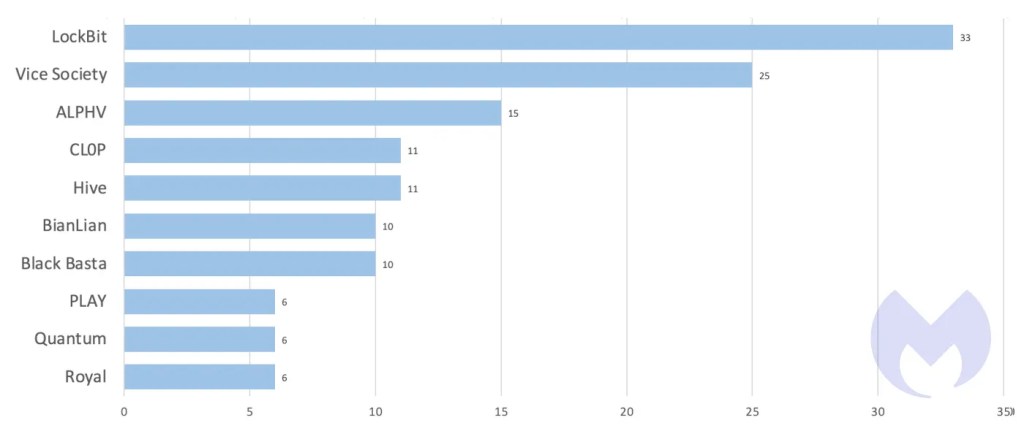

In 2022, LockBit was used in 31% of known attacks globally, 3.5 times more than its nearest competitor, ALPHV. (You can read much more about why LockBit is the number one threat to your business in our 2024 State of Malware report.) As you’d expect, given its global preeminence, LockBit was also the most widely used ransomware in the UK in the last twelve months.

However, in the UK, Vice Society was second, not ALPHV.

In fact, the UK is one of Vice Society’s favourite targets, accounting for 21% of the group’s known attacks in the last 12 months, a close second to the USA which accounted for 23%, and vastly more than the next country, Spain, which accounted for 8%.

Sadly, Vice Society’s disproportionate interest in the UK lands squarely on the education sector.

76% of Vice Society’s known attacks in the UK over the last 12 months hit the education sector, and Vice Society was responsible for 70% of known attacks on UK education institutions.

It is worth remembering that our numbers only reflect attacks where a ransom wasn’t paid, and the true number of attacks is far larger.

In 2023, the BBC reported on 14 schools in the UK that were attacked by Vice Society including Carmel College, St Helens, Durham Johnston Comprehensive School (hacked in 2021, documents posted online in January 2022), and Frances King School of English, London/Dublin.

Vice Society doesn’t reinvent the wheel in terms of how it breaks in to its victim’s networks. It uses familiar techniques such as phishing, compromised credentials, and exploits to establish a foothold.

Vice Society is also known to use legitimate software in its attacks, to avoid detection by security tools. This technique, known as “living off the land”, allows the gang to hide in plain sight on victim’s networks. One of the tools it favours is Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI), which is designed for administrators to manage and monitor computers from a remote location. The only effective way to spot attackers who are living off the land is with EDR software operated by trained security staff, or with a service like MDR.

We can only speculate about why Vice Society has such an appetite for UK schools, colleges, and universities, but we know the sector is not exactly awash with money. Education in the UK has suffered a significant drop in funding in the last decade, according to the non-partisan Education Policy Institute, which says that “between 2009–10 and 2019–20, spending per pupil in England fell by 9 percent in real terms.”

Following a spike in inflation in 2022, the UK’s largest teaching union voted to strike for better pay for its members. The strikes themselves are not the cause of education’s susceptibility to ransomware, but they are indicative of the deteriorating financial situation in UK education.

In 2021, this author interviewed a number of people involved in providing cyberprotection for UK schools. The picture in each was the same: Cybersecurity was one responsibility among many being carried by very small numbers of IT staff who were under tremendous pressure, and ill-equipped to fight off the attentions of a ransomware gang like Vice Society.

Conclusions

In the last 12 months there was no hiding place for organisations in the UK. Our analysis of total known attacks, known attacks per $1T of GDP, and known attacks per capita, shows that ransomware gangs treated the entire Anglosphere, not just the USA, as their prime hunting ground. As part of that group, the UK was on the front line against ransomware, and will almost certainly remain there.

Within the UK, the education sector was disproportionately affected. It suffered far more known attacks than education in France or Germany, and accounted for a much higher proportion of known attacks than education did in the USA. The vulnerability of the education sector was exposed by Vice Society, a ruthless ransomware gang with an outsized appetite for education targets. In the last 12 months, Vice Society was as active in the UK as it was in the USA. While LockBit remains the most dangerous ransomware in the world for almost all sectors in almost all countries, in the cash-strapped UK education sector Vice Society is the most dangerous predator.

The education sector in the UK should be alarmed that with an entire world of targets to choose from, ransomware gangs have singled it out for disproportionate attention. More than any other sector, it will need to rethink, reskill and retool its approach to ransomware to fend off the determined attentions of attackers who smell an opportunity.

How to avoid ransomware

- Block common forms of entry. Create a plan for patching vulnerabilities in internet-facing systems quickly; disable or harden remote access like RDP and VPNs; use endpoint security software that can detect exploits and malware used to deliver ransomware.

- Detect intrusions. Make it harder for intruders to operate inside your organization by segmenting networks and assigning access rights prudently. Use EDR or MDR to detect unusual activity before an attack occurs.

- Stop malicious encryption. Deploy Endpoint Detection and Response software like ThreatDown EDR that uses multiple different detection techniques to identify ransomware, and ransomware rollback to restore damaged system files.

- Create offsite, offline backups. Keep backups offsite and offline, beyond the reach of attackers. Test them regularly to make sure you can restore essential business functions swiftly.

- Don’t get attacked twice. Once you’ve isolated the outbreak and stopped the first attack, you must remove every trace of the attackers, their malware, their tools, and their methods of entry, to avoid being attacked again.